Capitalization Rules in Spanish | don Quijote

Welcome to a new academic article! This time let us begin with a bit of etymology. The Spanish word mayúscula (uppercase) comes from the latin word maiusculus, which means ‘bigger’. On the other hand, minúscula (lowercase) comes from the term minusculus, which means the opposite: ‘smaller’. That said, get ready to read about words that are written with ‘bigger’, uppercase letters (A, B, C, D…) and ‘smaller’ or lowercase letters (a, b, c, d…).

As a rule, Spanish is mainly written in lower case. In fact, the use of upper case is much more restricted than in other languages, such as English. Keep on reading to learn about capitalization rules in Spanish or click here to switch to the Spanish version of this post.

Uppercase Spanish Alphabet

To use Spanish uppercase letters properly, you need to know first how they look. If you can speak any other Latin-based language, the Spanish alphabet will look familiar. Except for the letter Ñ, it is pretty similar to the English one. These are the uppercase letters in Spanish:

A B C D E F G H I J K L

M N Ñ O P Q R S T U V W

X Y Z

How to Use Upper and Lowercase in Spanish

But let’s get down to the topic: when are Spanish words written with capital letters? RAE has published a complete guide on the use of uppercase and lowercase letters in Spanish. We have summarized that information a few points that will answer most of your questions.

Uppercase Words in Spanish

These are the types of words that are always written with capital letters.

1. First Word in Any Text or Sentence

Just as in many other languages, Spanish written texts begin with an uppercase letter. Want to know something interesting? You’ve probably seen sometimes a big, beautiful, hand-drawn letter at the beginning of ancient manuscripts. It is called an initial or drop cap, and it is an uppercase letter decorated in a special way that guides the reader through the text. Nowadays, we still use uppercase letters to start writing a text or to begin a sentence.

2. First Word after a Full Stop

As defined in the previous point, every word after a full stop is considered to be the beginning o a new sentence. For this reason, its first letter must be an uppercase letter. For example:

Hoy no iré. Mañana puede que sí.

(I won’t go today. Maybe tomorrow.)

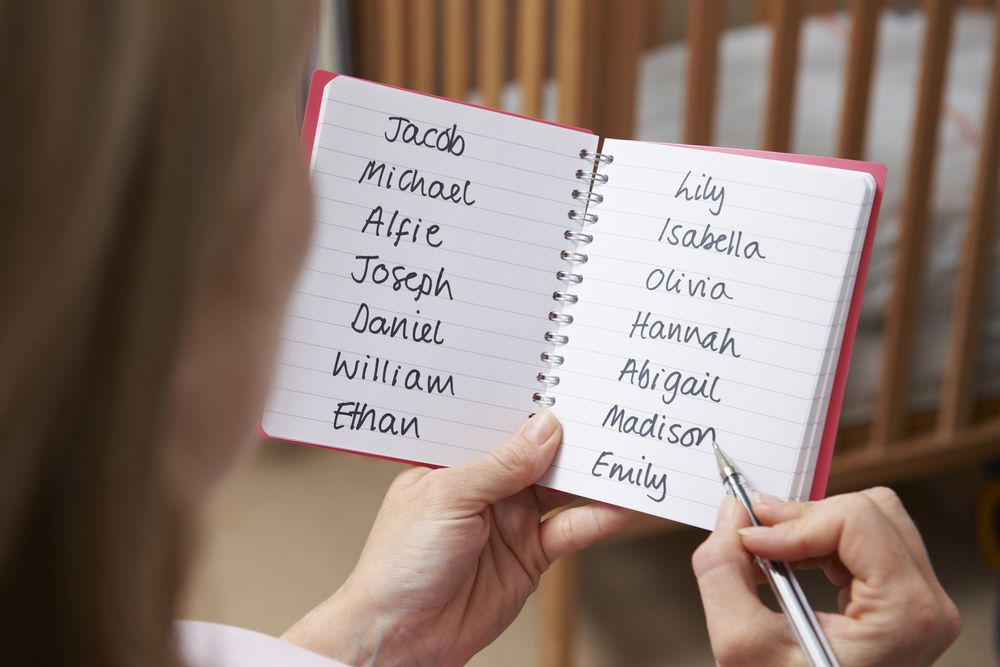

3. Proper Nouns

For example, people’s names and surnames (José Martín); countries, cities, and other place names (España, Buenos Aires, río Nilo); brands (Zara); institutions (Real Academia de la Lengua); galaxies, constellations, stars, planets, and satellites (la Vía Láctea, la Osa Mayor, el Sol, Mercurio); and zodiac signs (Aries).

4. Cardinal Points

The four cardinal points are written with uppercase letters in Spanish: Norte, Sur, Este, and Oeste, as well as their combinations (Noreste, Sudeste…) However, when we use this points merely as a reference, they are written in small caps. For example:

La brújula señala el Norte (The compass points North)

El norte de Europa es bastante frío (The North of Europe is pretty cold)

5. Abbreviations

Acronyms and abbreviations are always written in uppercase letters: UGT (Unión General de Trabajadore – a trade union), ONCE (Organización Nacional de Ciegos Españoles – a Spanish Foundation for blind people), EE.UU. (short for Estados Unidos).

Lowercase Words in Spanish

Due to English influence, many times we feel tempted to use uppercase letters when we are not supposed to, as the Spanish language doesn’t capitalize words that much. Here are some basic rules to avoid mistakes. What’s supposed to be written with lowercase letters?

1. Common Nouns

That’s an easy one to remember: coche (car), perro (dog), ordenador (computer)…

2. Generic Landmark Nouns

Streets (calle), promenades (paseo), avenues (avenida) as well as cathedrals (catedral) and other landmark-types. For example:

Vamos a dar un paseo por la calle Mayor (Let’s go for a walk around calle Mayor)

La catedral de Burgos es muy bonita (Burgos catedral is very beautiful)

3. Job Titles

Job titles such as rey (king), president (president), director, etc. are usually written in lowercase letters. However, it is pretty usual to see them capitalized when referred to a specific person, without mentioning his or her name. For example:

El presidente del Gobierno es Pedro Sánchez (The Prime Minister is Pedro Sánchez)

El Presidente anunció el otro día el cierre de las fronteras (The Prime Minister announced the border closure)

4. Geographic Features

Although the proper noun of certain geographical features is written in uppercase letters, the feature’s type (island, sea…) goes always in small caps. Let’s see a couple of examples:

El volcán Teide (The volcano Teide) El río Nilo (The Nile river)

5. Nationality

This is one of the most common errors using uppercase letters. All nationality adjectives, such as mexicano (Mexican), inglesa (English-female), española (Spaniard-female) or tibetano (Tibetan) are always written with lowercase initials.

Non-Standard Use of Uppercase Letters

Uppercase letters are often used to emphasize concepts. The netiquette (the way things are done on the Internet) marks that, when using all caps in the social media or in a chat, we are actually shouting.

Hope you found this blog post useful to decide whether you need to write uppercase or lowercase letters in Spanish. Thank you very much to Ramón, our Head of Studies at don Quijote Malaga, for putting his knowledge down to words. If you still have further questions, please leave a comment so we can work it out.